No Chardonnay, no matter how good, can match the purity, intensity and flinty character of Chablis, says Andy Howard MW, who takes an indepth look at the quality categories, range of producers and unique terroir of Burgundy’s ‘engine room’.

Originally published in the June issue of Decanter Magazine. Click to subscribe>>

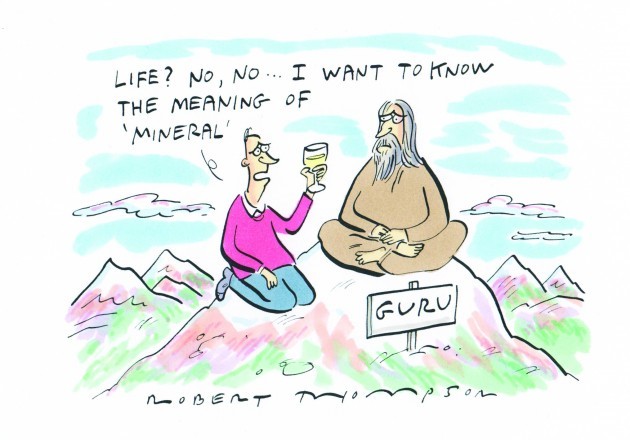

Chablis has always been one of my favourite wines and the crisp, mineral style – evocatively described by Hugh Johnson as the ‘crossing of a succulent wine with an austere soil to shimmering effect’ – is what makes Chablis unique for me.

The northerly location of the vineyards, closer to Champagne than the rest of Burgundy, and underlying geological structure impart a purity, flinty character and intensity rarely found in Chardonnay from other areas. Chablis is renowned for its ‘steely’ character, vibrant acidity, less overtly ripe fruit flavours and very understated (or no) wood influence.

Many top Chardonnay-producing regions around the world (Margaret River & Tasmania in Australia, Limarí Valley in Chile) have tried to emulate this style. Although these can be delicious, beautifully crafted wines, none that I have tried has the unique character that defines Chablis. It was this individuality which prompted me to write a dissertation on premier cru Chablis as the final stage in my becoming a Master of Wine.

Chablis is the engine room for the wines of Burgundy, accounting for 20% of all production with more than two-thirds exported. The focused and food-friendly style is highly popular with consumers in the UK, along with those from the US, Japan and northern Europe. Exports to the UK market (30% of total Chablis exports) rose by 23% to six million bottles in 2015. Chablis accounts for an average of 52% of white Burgundy sales in the past five years.

Nature’s onslaught

However, the marginal climate (which, combined with the unique geology of the area, bestows Chablis with its hallmark character) turned against producers in 2016. The devastation experienced during April and May 2016 will be a painful memory for many producers for many years to come.

On 27 April a particularly destructive frost hit the region. Normally the lower slopes are at risk from what Chablis producers refer to as white frost. On this particular night it was combined with a rarely seen black frost which came in over the high easterly plateau, devastating vineyards not normally considered to be at major frost risk. Large swathes to the southeast of Chablis were especially badly hit with the damage caused likened by some to the terrible frost of 1957 which almost wiped out the region. In that infamous vintage, the total production of grand cru amounted to one hectolitre – little more than 130 bottles of wine.

Just as vignerons were recovering last year, the region was hit by two major hailstorms. On 13 May the first struck about 400 hectares of vineyards mostly to the north of Chablis; the second (more destructive) storm arrived on 27 May, devastating vineyards to the southwest – particularly areas around the villages of Préhy, Courgis and Chichée. In some cases the whole vintage was lost.

Julien Brocard, of Domaines Jean-Marc Brocard, remained philosophical last October, stating that most Chablis producers would be able to survive nature’s onslaught – providing nothing similar happened in 2017.

Brocard noted that many Chablis producers considered themselves lucky. On the same late May evening a ‘supercell’ storm hit the nearby village of St-Bris, known for its Sauvignon Blanc. As a result, the total production of the St-Bris appellation in 2016 is likely to be zero.

Chablis lies on a geological structure known as the Paris Basin, a formation shared with Sancerre, Pouilly-Fumé and the Aube area of Champagne. All of these wineproducing areas are characterised by a band of chalky marl, combined with thin marl limestone (known as Kimmeridgian) and capped with harder Portlandian limestone.

The importance of Kimmeridgian soil was highlighted in 1923 when the French government’s wine tribunal dictated that only those vines planted on Kimmeridgian soil could be labelled as Chablis, with vines grown on Portlandian stone classified as Petit Chablis. This definition remained in place for more than 50 years. Kimmeridgian soil is the result of thousands of years of stratification of deposits dating back to the Jurassic age, most notably formed of fossil molluscs (exogyra virgule) as well as ammonites and other invertebrates. This is undoubtedly a key reason for the shellfish and flint character often associated with classic Chablis.

The quality levels

Chablis is broken down into four quality categories: Petit Chablis; village Chablis; a complex range of premiers crus from many different sites and expositions; and the grands crus, comprising seven individual climats.

Petit Chablis and Chablis account for 90% of production. Stylistically, Petit Chablis is a little less intense and displays a more fruitforward style best drunk young. Village Chablis should (but does not always) show greater intensity, focus and precision, usually with some Kimmeridgian derived salinity, a steely edge and cleansing acidity. Chablis can certainly be enjoyed young, but good examples from excellent vintages such as 2014 and 2015 will reward keeping for at least three to five years after the vintage. During my visit last October I had the fortune to taste many significantly older vintages, all of which had gained extra character and complexity without losing any of Chablis’ key characteristics.

For me, premier cru remains the truest expression of Chablis and offers great value for money for consumers compared to white wines at village and premier cru level from the famous appellations of the Côte de Beaune.

Hervé Tucki, brand ambassador for the highly influential La Chablisienne cooperative, emphasised the variety of all premier cru sites, with the influence of exposition, drainage and soil structure all imparting specific characters to the wines. In total there are 40 named climats for premier cru Chablis but in my view, Montée de Tonnerre is the finest, displaying power balanced with elegance and a pronounced mineral character. Another favourite of mine is Vaulorent – a small portion of the much better known La Fourchaume.

Vaulorent adjoins the grand cru climats of Bougros and Preuses but is little known outside of Chablis. This is a premier cru that should be on every Chablis lover’s tasting list.

Domaine Louis Michel, run since 2006 by the dynamic Guillaume Michel, is another producer renowned for focusing on individual terroirs. With more than 25ha of vineyards (including 14ha of premier cru), the domaine eschews any wood in order to let the character of the vineyard shine. Michel considers Montée de Tonnerre to be the most classic premier cru, but is also a great fan of the different terroirs found within Montmains.

This, like other popular premiers crus (eg, Vaillons and Fourchaume), can be divided into a number of other climats which may be labelled with either the ‘lead’ premier cru designation, or under their own name. Domaine Louis Michel bottles Montmains, Forêts and Butteaux within the Montmains premier cru. Montmains has a sea-breeze and iodine character; Forêts has more pebbles and less clay and (according to Michel) is more delicate and needs time. Finally, Butteaux has a more rustic style as a result of more clay and large blocks of Kimmeridgian deposits – ‘a Chablis for Chablis lovers’.

At the top of the Chablis hierarchy reside the grands crus, comprising seven climats on the prime Kimmeridgian slope to the northeast of the town (along with the eighth ‘unofficial’ climat of La Moutonne). Grand cru Chablis is undoubtedly a competitor to premier cru Puligny-Montrachet and Meursault, and offers great value in comparison. Grand cru has the concentration to absorb more wood than premier cru Chablis and, ideally, should be drunk after at least five years’ ageing. In its youth, the complexity of grand cru may not be immediately apparent – this only blossoms with time in bottle.

Top producers have holdings in many of the grand cru vineyards and although Les Clos is the largest and the most famous, discerning drinkers should experiment with some of the less well known sites.

Both Louis Michel and William Fèvre believe Vaudésir to be one of the more underrated climats. Another favourite for me is Blanchot, which differs to other grands crus in that its exposition is southeast on a very steep slope, resulting in real drive and focus in hotter vintages. Grenouilles is often more generous, fullbodied and accessible than other grands crus.

Producer diversity

Given the significant scale of production in Chablis, it is no surprise that there is great diversity in both size and type of producer. However, this is undoubtedly an area where large size does not detract from high quality. William Fèvre produces more than 1.5 million bottles in normal years with 500,000 of these from domaine-owned vineyards.

Virtually all Fèvre wines have some contact with wood – even Petit Chablis – although usage is extremely subtle in all cases. The contrast between the use of wood at Fèvre and its total exclusion at Domaine Louis Michel does not indicate that one producer is right and the other wrong. From tasting the full range at both producers, all the wines showed the classic style of Chablis. It is very much a question of philosophy and personal taste.

Other key domaines to consider include the Dampt family operations in the village of Milly to the west of Chablis, where father Daniel has his own label and vineyards as do sons Vincent and Sébastian. All three share the winery facilities, with a healthy competitive streak running through the family.

Milly is located next to the Côte de Lechet premier cru and, not surprisingly, all of the Dampt family wines are great examples of this distinctive terroir, as well as the adjacent premier cru Vaillons. Further to the west, in the direction of Auxerre, one finds the excellent Domaine Louis Moreau in Beines, along with the great value wines from Domaine Alain Geoffroy.

The influence of larger Burgundian houses from the Côte d’Or is evident too, with the recent takeover of Domaine Billaud-Simon by Faiveley, along with the earlier purchase of Domaine Long-Depaquit by Maison Albert Bichot. Such acquisitions should be viewed as very positive for the region. Recent major investment by Bichot has seen the introduction of extensive whole-bunch pressing at Long- Depaquit, a development that is greatly exciting to winemaker Matthieu Mangenot.

Many other domaines remain resolutely family orientated. Louis Moreau is a sixthgeneration winemaker; Domaine Seguinot- Bordet (run today by president of the Chablis growers Jean-François Bordet) was created in 1590; while at one of the top addresses in town – Domaine Jean-Paul & Benoît Droin – Benoît represents the 14th generation to make wine since 1620.

Finally, no survey of Chablis producers can be complete without recognising the acidity will repay careful ageing at nearly all quality levels. Despite some short-term prices rises, and some potential shortages in supply, quality remains at an all-time high and Chablis continues to offer great value compared to other white Burgundy. The best way to support producers suffering from the traumas of 2016 is to keep buying these excellent, unique wines.

Read on the next page:

Chablis: know your vintages

Translated by ICY

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit